Maybe linguists *do* know a lot…

“You’re a linguist? How many languages do you know?”

It’s a pet-peeve of most linguists I know. There are support groups and memes and blog posts devoted to it (even, mind you, one of mine. *cough*). Linguists bluster in, “WE’RE LINGUISTS, DAMNIT! NOT POLYGLOTS! WE DON’T KNOW ANY LANGUAGES!”

[insert Chomsky slam here]

ANYWAY… I used to be on the monoglot-linguist bandwagon. My official position was that,

Although some linguists speak two or three or more languages, most of the linguists I know only speak English and, furthermore, of those linguists who do happen to know multiple languages, their polyglot gift doesn’t usually have much to do with the work they do as linguists. (via)

Well, I’ve since changed my mind. Or, rather, I think we (linguists) have been approaching this “linguist~polyglot” confusion from the wrong angle. I think it’s time for us linguists to reevaluate what we’re hearing, what we’re saying, and why we think we’re right. Consider this…

When someone asks how many languages I speak, here’s my usual response:

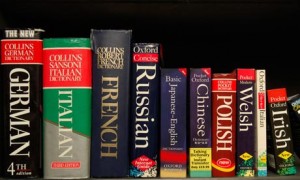

“Oh, I only speak English, and I’m not great at that! haha! But yeah, just English. I mean, I’m okay with Spanish, and I have a passable command of French, well, passable enough for Paris, anyway. And I’ve studied Japanese and Hebrew, and I know a surprising amount of German for someone who’s never taken formal classes, and, oh yeah, Old English, Esperanto, Russian, and Klingon are in there, too.”

To a linguist, this sounds just like I think it does (probably because I’m a linguist)—the only language I speak is English. But how does this sounds to a non-linguist? As a comparison, when I ask someone, “How about you? Do you speak any other languages?” The responses I hear are more like this:

“Well, I took French in high school. Je m’appelle Christine. Quelle heure et-il?” or

“Well, I took French in high school. Je m’appelle Christine. Quelle heure et-il?” or

“When I was stationed in Japan I learned to say Anata no kao wa inu no yō ni miemasu. It’ means You have the penis of a sad monkey hahah.” or

“My great-grandmother was Cherokee Indian, and when I hear somebody talking Indian, sometimes I feel like I can pick out a word or two. Because it’s in my blood, y’know?”

That last one is a whole nother blog, but for now, THE POINT I’M TRYING TO MAKE is that people, regular non-linguist people, don’t have the same set of references for what it means to “speak a language” as linguists do. Even on the most basic level, linguists and non-linguists aren’t on the same page… to a linguist “speak a language” and “know a language” mean very different things (even though we often play fast and loose with them).

To a linguist, KNOWING a language is about acquisition and mental representations and the way that structures in the brain are activated; the things a person KNOWS about a language are things that we’re largely unaware of— “big red rubber ball” sounds correct while “rubber red big ball” doesn’t. How do you know that? Because you know English. For most linguists, you can only really KNOW a language that you acquire in childhood. On the other hand, SPEAKING a language is an entirely different ball of wax. SPEAKING a language involves levels of proficiency and communicative competence and memorization of rules and vocabulary; learning to SPEAK a language is a very active, conscious, deliberate process. It is, in many ways, the opposite of KNOWING a language.

But, to most people, KNOWING a language isn’t just similar to SPEAKING a language, it’s damn near the same thing. And from the perspective of a western educational system, that’s a perfectly reasonable conclusion to reach. After all, people aren’t trained in linguistics in high school, but they are often trained in foreign language learning, and in high school Spanish, the difference between knowing Spanish fluently and knowing “a little” Spanish is one of degree, not kind. Want to know more Spanish? Memorize more vocabulary. It’s as easy as that.

From there it’s real easy to get to “Well, I know one sentence in Swahili, so I guess I know Swahili. I just need to learn more words, right?”

From there it’s real easy to get to “Well, I know one sentence in Swahili, so I guess I know Swahili. I just need to learn more words, right?”

All the linguists throw up their arms in exasperation! How can anyone be so daft! Of course you don’t know Swahili, you peasant!

But here’s the twist; I think they (the non-linguists) are right. I know a couple words in Basque—far more than most North Americans, I’d wager—so perhaps I do “know a little Basque”. Or, playing by the rules of linguistics, I’d say that I’m a native speaker (whatever that means) of one language, but by any reasonable definition, I speak two or three (or six or seven). And I think that if we (linguists) would really sit down and have a think about it, we’d find that we’re all peeving over something that we can’t easily defend, even with our own tools. Allow me to explain…

From the perspective of a nativist, acquisition-device, Chomskyan view of language, anything you don’t acquire in childhood is already patently different than your “first language”. Learning Spanish in high school is *by definition* not acquisition, it’s rote-memory. Yet we (linguists) are pretty okay with saying that someone who learned Spanish in high school, took Spanish as their major in college, and now lives in Miami and speaks Spanish more often than English gets to count as someone who “speaks Spanish”. This hypothetical person “speaks” two languages. I doubt I could find any linguist who’d disagree. Does that person KNOW Spanish? Well… I think how you answer that depends on your religion. Regardless, here we have a person who really is different only in degree from someone who knows little more than Mas cerveza, por favor. That is, if we already accept the acquisition-device premise, then learning by memorization is learning by memorization; we’re just quibbling over where to draw the line in the sand.

On the other hand, from the perspective of a functionalist, neo-Skinnerian view of language, everything is pattern matching and there isn’t any meaningful difference between first language acquisition and high school language learning, anyway (except for maybe ease and brain plasticity, but, y’know… that’s a different department). So, again, we come back to a difference in degree, not kind. What separates Einen kebab, bitte and being able to live comfortably for the rest of your days in Bremen is the difference between the bottom and top of the same language ladder; one person has just climbed higher.

See where I’m coming from? Regardless of how you theorize language learning, it’s not the non-linguist plebes that are getting it wrong, it’s us— it’s the linguists.

Linguists, more than most academics, seem to hold a set of Sacred Propositions that we never bother to question—

• all languages are equally complex;

• all languages are equally complex;

• you don’t know what passive voice is;

• media doesn’t don’t influence language change;

• linguists don’t speak a lot of languages;

• knowing how to say a single phrase in a language doesn’t mean you speak that language…

—except… well, we can’t prove any of them. We’re making objective statements about The Truth of Things, and not only do we (linguists) not have proof, we’ve never even bothered to define the terms very well.

So, here’s my suggestion…

Non-linguist people: next time you’re on a plane and discover that the person you’re having armrest war with is a linguist, don’t ask them how many languages they know. Don’t ask them how many languages they speak. Ask them how many languages they’ve studied. They’ll love that.

And linguists? Consider this: the path to public understanding is a long one; maybe it’s time we get off our high horses and do a little leg work for a while.